Ghazal Cosmopolitan

Poetry is of course a universal art, but is it possible for a particular poetic form to be not only universally (or largely) adaptable but also act as a vessel for the mercurial shifts that define the cosmopolitan? As I delve into the history of the ghazal form, I find that it has effectively transcended and transferred the culture of its origins and made itself at home in vastly different cultures and times.

Two recent scenes come to mind as I think of the ghazal and the poetic cosmopolitan:

Latin Quarter, Paris: Marilyn Hacker weaving in and out of Arabic, French, and English at a Lebanese restaurant in the heart of medieval Paris, before she and I walked through the backstreets, through the doors of the somber Saint-Séverin Saint-Nicolas church where she lit a candle, to Berkeley Bookstore where she recited her ghazal dedicated to a Pakistani and an Afghan woman.

Princeton, New Jersey: Dr. Azra Raza’s poignant account of how she told her taxi driver to stop and wait outside while she rushed to view Einstein’s garden, paying homage to him by reciting Ghalib’s ghazal verses—the most befitting tribute Raza, a well-known research scientist, author, and an aficionado of Urdu literature, could offer.

The two scenes collapse and expand in the same spectacular way as a ghazal couplet or sher does; these moments capturing convergence in divergence, the dance of the “contraries,” bringing together science and art, politics and spirituality, geography and history, East and West, led me to explore cosmopolitanism at the root of the ghazal form.

Cosmopolitanism is defined in the dictionary as “being free from local, provincial, or national ideas, prejudices, or attachments; at home all over the world”; it is necessarily an active appreciation of disparate entities, a rejection of narrow constructs of identities, in fact, a rejection of all strictures; it is an ownership as well as a divestment. It celebrates pluralism as fiercely as it forges an autonomous voice.

The ghazal, in its structure as well as its sensibility, not only allows contraries to cohabit but, in the best compositions, makes a demand to frame polarity in the same space. Once the matla, the opening couplet, introduces the refrain (or radif), the reader expects two things: one, that each successive couplet will be locked in by the same phrase/word/image of the radif, and two, that a wild freedom of perspective will be offered like a new puzzle piece that astonishes by fitting the given radif as perfectly as the previous one.

The ghazal registers order, follows it, and revels in agitating it—a kind of duende in its genetic code. Click to Tweet

Click to Tweet

The two scenes above provide a launching point for this discussion on the ghazal’s cosmopolitanism because I see the concerns of the classical ghazal enacted in them. And ghazal is nothing if not performative, a collaboration of sorts with the mushai’ra audience: another facet of its cosmopolitanism. Azra Raza, director of the MDS Center at Columbia University and co-author of Ghalib: Epistemologies of Elegance, appears to me to enact the ghazal by paying tribute to both Einstein and Ghalib, two great people from different parts of the world, engaged in radically different enterprises, who would have completely understood each other’s urgent desire to reach an unnervingly elegant question through boldly exercising the imagination, who were not only unafraid of polarities but found meaning in placing polarities in close proximity to each other. Marilyn Hacker, long and deeply invested in a poetics of challenging dichotomies, appears to do the same by combining diverse gestures, merely out of habit; volume after volume of her poetry and translations, from earlier works to the more recent Names and Diaspo/Renga (co-authored with the Palestinian American poet Deema Shehabi), offer us insights into how to grow a robust, original thought in the thinnest cracks of established order.

The ghazal registers order, follows it, and revels in agitating it—a kind of duende in its genetic code.

The ghazals of Ghalib and Marilyn Hacker may be hundreds of years apart and belong to two very different cultural traditions and historical realities, but the cosmopolitanism they espouse is appreciable as a powerful and enduring gesture. Both lavish their ghazals with a polyglot sophistication backed by extensive knowledge and an unabashed love of humanity.

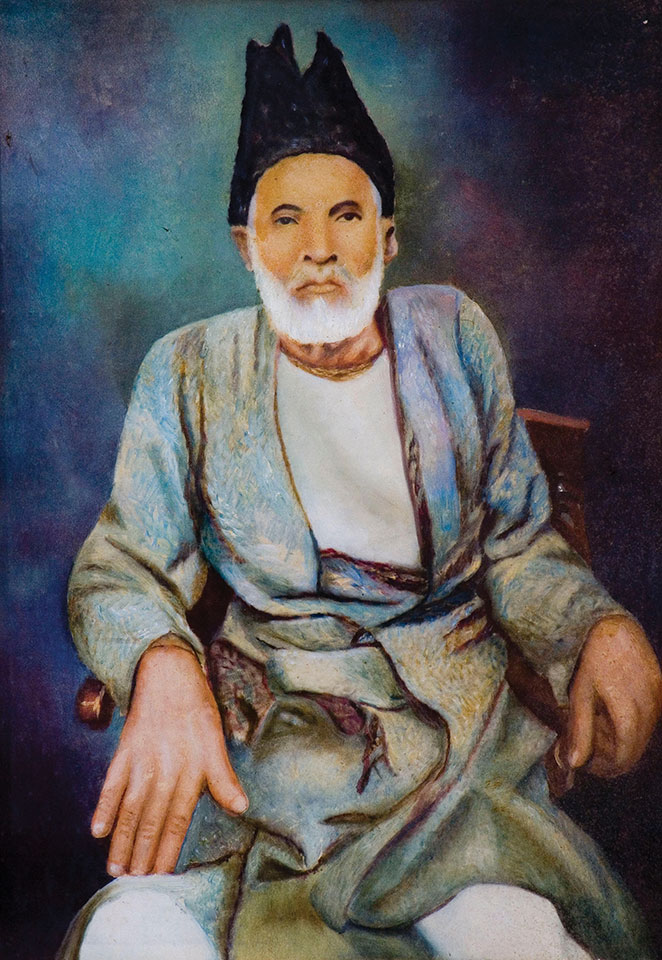

Ghalib (1797–1869), known as the master of the ghazal, is still little known in the contemporary mainstream ghazal culture in America, though the ghazal, as we know it here, originated as a response to Ghalib’s nineteenth-century Urdu compositions nearly half a century ago. In fact, the American ghazal’s “birth” as a poetic form actually coincided with the centenary of Ghalib’s death as Aijaz Ahmed began the ghazal-translation project (ahead of Ghalib’s death-centenary in 1969) involving Adrienne Rich, W. S. Merwin, William Stafford, and others. Ahmad, as a native speaker of Urdu, supplied the literal translations of the ghazals, along with the necessary lexical/cultural notes to the American poets who were asked to render the literary translations. What was originally intended as a project of translation inevitably ended up becoming trans-creation, almost wholly new work with a faint trace of Ghalib’s original. It was not until Agha Shahid Ali reintroduced the ghazal form decades later, explaining all the rules (and the cultural codes/context behind them), that “real American ghazals,” in Ali’s words, were produced in America.

A discussion of the ghazal’s cosmopolitanism must include a brief history of the ghazal and its transmutations from the original Arabic: the earliest ghazals were romantic odes included as one of the segments of the qasida—a long, multisegmented poem written in monorhyme (with a set of predetermined themes) that sixth-century Arab Bedouins composed as their caravans traveled from oasis to oasis, reciting these poems at campsites. With Islamic conquests, both the qasida and the ghazal traveled eastward as well as westward and adapted to cultures as varied and distant as Spanish, Indian, German, Turkish and was utilized in numerous languages and dialects across the world, but the ghazal’s Persian transmutation/iteration came to be definitive. Urdu, a relatively new Indian language and a hybrid of Arabic, Sanskrit, Persian, and Turkic dialects, absorbed the Persian ghazal quite early in its evolution, thanks to the thirteenth-century poet Amir Khusrau Dehlawi, son of a Turkic nobleman and an Indian courtier’s daughter.

An aspect of cosmopolitanism is the availability of a rich lexicon as well as a network of idioms and metaphors yielded by a literary heritage that is built on cultural exchange, among other things. Historically speaking, such a standard is met by languages that have had imperial privilege. Arabic, Persian, English, and to a large extent Urdu are among such languages. By Ghalib’s lifetime, Urdu had been in use by the royalty and nobility (though Persian was the official language of the empire), was passing through its golden age of poetry (with ghazals at the forefront), and was the language of choice by the poet-emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar himself. A language that reflects imperial power must also include a lexicon to express the tensions and grief caused by it; Urdu most certainly does. Even Bahadur Shah, in exile after the fall of the Mughal empire, wrote in a famous signature couplet: “How unfortunate you are Zafar, failing to procure for burial / two yards of land in the beloved’s neighborhood.”

Hacker is writing in a historical period that has seen tectonic shifts in terms of global power, but the world is a very different kind of dystopia since Ghalib’s times.

The cultural gifts of empire are counterbalanced with the angst and the equalizing forces of democracy in the lexical makeup of a language; this is true for both Urdu and English as imperial languages. Ghalib belonged to the cusp of empires: Urdu’s renaissance, Mughal decline, and the seizing of power by the British. His ghazals are colored by a wide range of moods, some of which reflect the devastations of his times. Hacker is writing in a historical period that has seen tectonic shifts in terms of global power, but the world is a very different kind of dystopia since Ghalib’s times.

Among the cosmopolitan features of the ghazal are (1) each couplet being autonomous in theme and tone, affording a special level of individuality to the poet, and to each sher of his/her ghazal, which can be quoted separately, (2) no upper limit to the number of couplets allowing each ghazal to be of unique length, (3) the self-addressed “signature” couplet, a relic from the ghazal’s ancient oral tradition but valuable as a personalizing device in the contemporary/cosmopolitan context of fighting sameness and the anxiety of losing individuality.

A singular trait of Ghalib’s cosmopolitanism is his irreverence, which has a mystic interrogation at heart, such as in these lines (in literal translation):

Granted they are not a lover of God, yes, they are unfaithful

Whoever holds creed and heart dear, do not dare to wander up their way

(Raza/Suleri-Goodyear, Ghalib: Epistemologies of Elegance)

Once again the decorum of forbearance causes suffocation

It has been years since I had the luxury of tearing my clothes in grief

(Raza/Suleri-Goodyear, Ghalib: Epistemologies of Elegance)

Hacker has a similar impulse while negotiating the true and the false beloved:

Lines that grapple doubt, written because of the beloved:

when grief subsides, what survives the loss of the beloved?

Who signed the warrant that scaled you in this cell?

Who read your messages? Who was the boss of the beloved?

How pure you were, how abject you are now,

waterboarded after the double-cross of the beloved

(“Ghazal: Beloved”)

Any ghazal lines in which the beloved is mentioned and the Almighty suggested as the beloved must be interpreted in multiple ways, ghazal-fashion. The above lines by both poets can certainly be read in several ways.

Scholars agree that Ghalib is a poet’s poet; his ghazals explore paradox, esoteric themes, multiplicity of meaning, literary humor, spiritual angst, desire to grapple with mysteries, battle with the limitations of language. He often juxtaposes symbols of religion, mocks or switches them around in order to emphasize spirituality over religion. Another moment of cosmopolitanism in how he weds polarities:

In the Kaaba I will play the conch-shell

In the temple I have draped the “ahram”

(Pavan K. Varma, Ghalib: The Man, the Times)

Steadfast devotion is the foundation of all faith;

If the Brahmin dies in the temple, bury him in the

Kaaba

Or again,

In the rosary or the sacred thread, no special grasp is threaded;

It is the devotion of the Sheikh and Brahmin that are to be tested

(Pavan K. Varma, Ghalib: The Man, the Times)

The refusal to exclude (in order to appease the establishment) is a cosmopolitan gesture one comes across again and again in Hacker’s ghazals as well:

The diplomat entering the leader’s office

forgets the Copt, the communist, the Kurd outside the door.

The revolutionary’s nameless laundress

wonders “What happens to a dream deferred?” outside the door.

Like Ghalib, Hacker personalizes the ghazal with the first and second person and uses image to enhance the energy of the radif; often the images work as metaphors, are associative, and carry the irony of the contraries, as the following couplets in which a receding bus (full of sodden passengers) is a subdued image despite its physical largeness because it is elusive and represents a departure, in comparison to the next couplet in which a small motorcycle makes a noise that shatters the speaker (like the beloved’s absence). “Babies” similarly suggest the vulnerable, intimate, and small against the largeness of “countries” and “war,” but the loss or absence of the intimate is always the largest:

The bus heads eastward with its sodden passengers

out of my vision like a metaphor across the street.

I write “you,” shorthand for one more absence.

A motorcycle revs up with a roar across the street.

If they imagine women forget dead babies

in those countries, they don’t imagine war across the street.

The juxtaposition of largeness and smallness, located at the hinge between the couplets, comes across as cinematic (and therefore cosmopolitan). Ghalib offers a similarly telescopic moment:

What appears as confirmation of the Ocean’s actuality

Is merely a sum total of wave, drop, phosphorescence

(Raza/Suleri-Goodyear, Ghalib: Epistemologies of Elegance)

And Hacker:

History, a child at the chapter’s cusp

Will only find out what transpired by waiting.

Ghalib’s ghazals are extremely difficult to translate in verse; his cosmopolitanism, as framed and enriched by the ghazal’s parameters, is difficult to appreciate fully in a literal translation. But in the case of both, Mirza Ghalib in Urdu and Marilyn Hacker in English, the ghazal provides the flexibility, the economy, and the hinge that joins contraries—keeping them apart, keeping them together, keeping the cosmopolitan intact.

Carlsbad, California