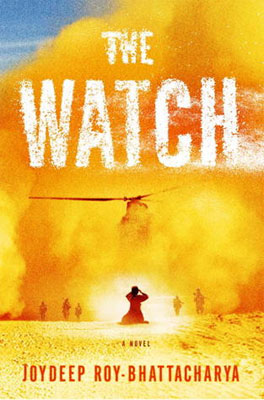

The Watch by Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya

New York. Hogarth. 2012. ISBN 9780307955890

At the beginning of The Watch, Nizam, a young woman from a mountain village in Afghanistan, arrives in a clearing outside a US outpost, using her hands to push the rickety cart carrying her legless body over the rough terrain. To the troops, who recently took casualties during a raid on their outpost, Nizam poses an unprecedented problem. Like Antigone, she demands the corpse of her brother from an unrelenting ruler so that she can perform burial rites. More profoundly, her presence as a woman in terrain defined by the actions of Afghan and foreign men transcends any security risk she might pose—perhaps as a suicide bomber, perhaps as a lure to get soldiers in range of insurgent snipers—and calls into question the very humanity of the men waging war in her country. In the novel’s first chapter, Nizam articulates the quandary she poses. After a soldier watching her bury a body in the clearing makes the sign of the cross, Nizam thinks, “It’s a small indication of humanity. And yet, all afternoon, I smell the inhuman scent of their guns.”

At the beginning of The Watch, Nizam, a young woman from a mountain village in Afghanistan, arrives in a clearing outside a US outpost, using her hands to push the rickety cart carrying her legless body over the rough terrain. To the troops, who recently took casualties during a raid on their outpost, Nizam poses an unprecedented problem. Like Antigone, she demands the corpse of her brother from an unrelenting ruler so that she can perform burial rites. More profoundly, her presence as a woman in terrain defined by the actions of Afghan and foreign men transcends any security risk she might pose—perhaps as a suicide bomber, perhaps as a lure to get soldiers in range of insurgent snipers—and calls into question the very humanity of the men waging war in her country. In the novel’s first chapter, Nizam articulates the quandary she poses. After a soldier watching her bury a body in the clearing makes the sign of the cross, Nizam thinks, “It’s a small indication of humanity. And yet, all afternoon, I smell the inhuman scent of their guns.”

Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya writes each chapter of this novel from the point of view of a different character. In all except two chapters, the novel represents the war in Afghanistan from the perspective of the Americans who find themselves in almost surreal conditions, marked not only by extremes in climate and cultural difference but also by sleep deprivation and haunted dreams that frequently transpose combat and domestic experiences. Lieutenant Nick Frobenius suggests the impossibility of the American position in Afghanistan (and, by implication, in the war on terrorism). Educated in the classics and driven by idealism, Frobenius tries to make sense of the war’s brutality: “I cannot succumb to the illusion that there is no larger meaning to this war, no essential truths.” And yet Frobenius also remarks that ours is “the age of Creon. He’s the government and the corporations and everything else that matters. He’s a machine, a system, he has his own logic, and once you’re part of that, it really doesn’t matter if you’re a grunt or a general: you’re trapped in a conveyor belt of death and destruction.”

The untenable contradiction be-tween higher ideals and a world governed by Creon finds lyrical expression when Nizam plays a stringed instrument called a rebaab in the forlorn night. After the music stops, an officer observes that “nothing stirs, and no one seems to want to be the first to break the silence. In all of my years with the company, I’ve never seen the men remain so still and for such a long period of time.” Such moments of beauty and reflection, however, come surrounded quite literally by the fortifications that separate these heavily armed men from the vulnerable Nizam. As does Antigone, Nizam ultimately meets an inglorious and inhumane fate, for which the humanizing effect of her music is small recompense.

Jim Hannan

Le Moyne College