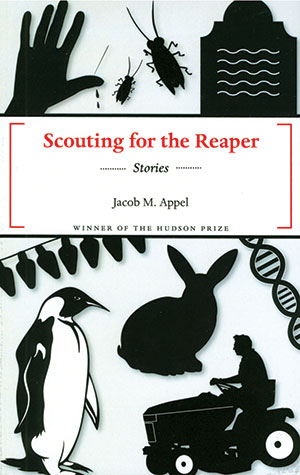

Scouting for the Reaper by Jacob M. Appel

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Black Lawrence Press. 2014. ISBN 9781937854959

After publishing several novels, a volume of essays, and over two hundred short stories in literary journals and anthologies—winning a number of prizes along the way—Jacob M. Appel rewards readers with a collection of seven new short stories. The book has won the Hudson Prize, awarded by the Black Lawrence Press.

After publishing several novels, a volume of essays, and over two hundred short stories in literary journals and anthologies—winning a number of prizes along the way—Jacob M. Appel rewards readers with a collection of seven new short stories. The book has won the Hudson Prize, awarded by the Black Lawrence Press.

The title story is narrated by a teenager who dresses in a Girl Scout uniform (too small), pretending to be eleven, to help her father sell gravestones. She lugs the sample case of different kinds of stone to each house. The pretense that she has just come from a Girl Scout meeting with her father helps establish his credentials as a caring parent. She says nothing, of course, while her father builds on this impression in making his pitch.

The twist in this story, and in several other stories, is that a youth, sometimes narrating years later, realizes that one of his or her parents has had a relationship with another person, and it still matters, even if the formerly beloved is obviously using the parent. This relationship impinges on the youth’s own sexual awakening. The youth is at the age when he or she can actively imagine that some just-met person “will become my husband (or wife).”

Fathers loom large in many of these early stories, whether in crisis or impacting the youth’s own life. Mothers and marriages are fretful; where they are protagonists, women are older, childless, or with grown children who are distant. They react emotionally, but understandably, to separation from what they know or have chosen, whether it be a longtime yardman or a pet rabbit suddenly gone blind.

Apart from the title story, “Ad Valorem” and “The Vermin Episode” stand out for creating discomforting sympathy with each protagonist—a woman recently widowed and a rabbi, respectively. The woman is attracted to an accountant who has been doing the couple’s taxes for years. Before she commits to a relationship with this man, also widowed, she wants to double-check his work. It’s easy enough to do, given that her deceased husband kept photocopies of all the business receipts. But she worries about what she will do if she finds the accountant has cheated them. The second story is both a delightful and serious riff on Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis.” What can a well-meaning rabbi do with the remains of a large dung beetle after he has promised Mr. Samsa that he will have Gregor buried in a proper cemetery?

Whether they realize it or not, the narrators of these stories explain themselves well, no longer the silent children listening to their parents or less assertive adults imposed upon. All seek or cling to something that affirms their lives, even while waking to unforeseen responsibilities.

After reading so much contemporary fiction that is fretful, laboring in the shadow of modernist complexity or postmodern minimalism, there is solace in reading stories that beckon one into the lives of characters in situations that naturally evolve from satisfying plots.

W. M. Hagen

Oklahoma Baptist University