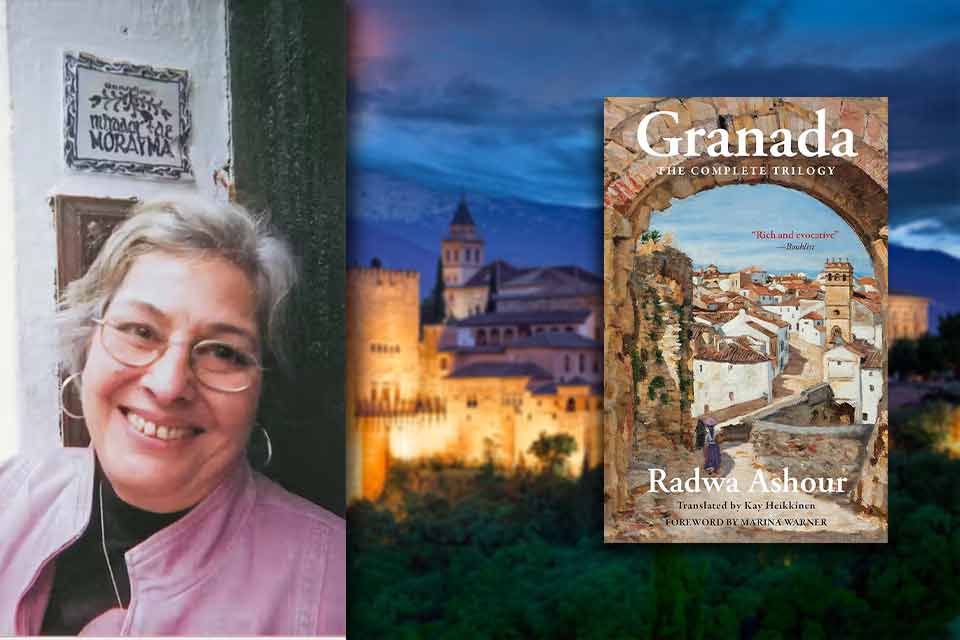

Like Gold in the River: A Review of Radwa Ashour’s Granada Trilogy

Years ago, I visited the Alhambra in Granada and was awestruck by the grand palace and fortress that was built during the historic Islamic period in Spain. Standing on a plateau, the palace overlooks Albaicín, the quarter of the old Moorish city nestled in the nearby hills. I remember thinking at the time that I knew very little about this golden era of Islamic history. Scholar and creative writer Radwa Ashour’s novel Granada gives readers insight into the fabric of daily struggles and drama for ordinary Arabs who lived at the end of Muslim rule in Spain and were persecuted during the Spanish Conquest and Inquisition. This ambitious novel was recognized when it was first published in Arabic in 1994: part 1, Granada, won the Book of the Year at the Cairo International Book Fair. The following year, in 1995, the entire trilogy won first prize for the best book by an Arab woman writer. William Granara’s translation of Granada, published by Syracuse University Press, first made this novel accessible to an English-speaking audience in 2003.

More than twenty years later, Hoopoe Press has now published the complete trilogy, Granada, Maryama, and Departure (2024), translated by Kay Heikkinen. Ashour’s Granada is a historical epic whose themes still resonate powerfully in the present: the erasure of cultural heritage and identity by occupiers, armed resistance, disappearances, imprisonment and execution of political prisoners, forced marches and expulsion. But the novel also celebrates the heroism and determination of normal people who maintain their Arabic language, cultural and religious traditions and rituals through storytelling, learning and teaching, even under the yoke of a repressive regime.

The opening of Granada begins with the image of a naked girl in the street, an omen of impending political chaos as Muslim rulers relinquish their long-standing empire to the Castilian throne and church. Rumors abound about Christian soldiers entering Granada. The naked girl is then found murdered. Enslaved prisoners are paraded through the streets. The description of Granada in July 1499, before the Bishop of Toledo arrives, highlights the artfulness of Kay Heikkinen’s translation, which reflects the metaphoric grandeur of the original Arabic: “Summer in Granada is olive trees setting fruit, coquettish apricots appearing and then hiding among the green leaves, pomegranates gathering their sweetness slowly before splitting open in the hands of the people eating them.”

After the bishop’s arrival, forced conversions quickly follow. In our contemporary reality where the zeitgeist focuses on the importance of social media, algorithms, and AI, it is particularly moving to read about Abu Jafaar, a bookseller who is committed to saving his cultural heritage. He hides valuable Arabic manuscripts from the Spanish occupiers; however, many books are not saved. He witnesses the desecration of the Qur’an and then its destruction as it is burned. The scene is so shocking that it shakes his belief in God, and he tells his wife, “I will die naked and alone, because God does not exist.” Destruction of books is just one strategy that religious or political authorities employ to demoralize citizens whose beliefs have been deemed unacceptable.

Destruction of books is just one strategy that religious or political authorities employ to demoralize citizens whose beliefs have been deemed unacceptable.

Even though Abu Jafaar dies early in the novel, his influence is palpable. For example, he had encouraged his granddaughter, Salima, in her studies. Her grandmother is more excited about her marriage to Saad, the adopted son of Abu Jafaar. Despite her initial lack of enthusiasm, Salima marries Saad, who becomes a resistance fighter, and they develop a relationship; however, they lose their first baby. Salima’s brother, Hasan, falls in love with a gypsy storyteller, Maryama. Salima carries on her grandfather’s legacy in her tenacious quest for knowledge. She is frustrated that she only has access to five books, one of which is al-Hussein ibn Abdullah’s books, The Canon of Medicine. Salima reflects: “She was stifled in the prison of a vile time when acquiring books was a crime subject to punishment, when study required caution and concealment, not only to deceive the eyes of a stranger who might be lying in wait, but able to deceive those near her.” How poignant to think about the hunger and thirst for books, when we struggle to convince students at the university to read a few pages! Salima secretly buys Ibn al-Baytar’s Compendium, an encyclopedia of herbs and plants. With her newfound knowledge, she becomes a healer and is sought after by those who are in sick and need. She is briefly reunited with her husband, Saad, and gives birth to a daughter named Aisha. Later, Salima is arrested and brought before the Inquisition, accused of being a witch and having intimate relations with a goat. Descriptions of her interrogation and imprisonment remind me of the character Blimunda in José Saramago’s novel Balthasar and Blimunda. Despite the lack of evidence against her, Salima is still burned at the stake.

But there are other restrictions as well. The Spanish close all the bathhouses. The Spanish king declares that Muslims must convert or emigrate. Hasan’s wife, Maryama, refuses to leave. The family converts to satisfy the authorities, but the conversion meant that circumcision, funeral rituals, celebration of Ramadan, and other religious holidays were all “criminal offenses.” Maryama, a colorful raconteur, is skillful at evading authorities and practices a double life in order to maintain cultural traditions. In contrast, Naeem, the other adopted son of Abu Jafaar, goes to the “New World” with a priest, Father Miguel. Naeem witnesses the cruelty of Spanish colonizers in their dealings with Indigenous peoples. Naeem feels the irony when he sees Father Miguel doggedly working on a diary of his experiences in the New World without knowing the language of these people. Meanwhile, Naeem falls in love with an Indigenous girl, Maya, and struggles to communicate with her.

Part 2 of the trilogy focuses on Salima’s sister-in-law, the flamboyant Maryama, and the descendants of Abu Jafaar. Maryama begins to have dreams and feels the presence of Salima, the self-taught doctor, in the house. Hasan welcomes Naeem who has returned from the “New World,” broken and old, almost unrecognizable, obviously suffering from trauma because of the death of his wife, Maya, and children by the Spanish. Naeem thought that returning to Granada would heal his alienation, but it does not. He tells Ali, Salima’s grandson, stories from the Islamic tradition.

The theme of preserving cultural heritage falls to Hasan, Salima’s brother. He starts to worry that his grandson is becoming too immersed in Spanish culture and Christianity and decides to teach him Arabic. They move to Aynadar, where more Arabic books were hidden by the family. The boy thinks, “Only old books locked up as if they were Solomon’s treasure.” In his immaturity, Ali thinks that the only treasure is like the gold in the Arabian Nights tales.

There is another failed revolt. The Spanish march to Granada. The hundred nobles who led the revolt against the Spanish are killed in prison. The Spanish insist that the inhabitants of Granada move to Córdoba. In the forced march, Ali’s grandmother, Maryama, dies. Ali flees from the march soon after.

The family torch then falls to Ali, Salima’s grandson, who learns that his father, Hisham, whom he never met, was a resistance fighter. Once he returns to Granada after five years, he does not see anyone that he recognizes, except an old childhood friend, José. The Spanish encourage the Arabs to return to their homes in Granada, but the homes are no longer theirs. José has taken possession of his family house and the title but allows Ali to live there. Ali is then arrested by the Inquisitors because his father is a “bandit,” and he spends over three years in prison.

The Spanish encourage the Arabs to return to their homes in Granada, but the homes are no longer theirs.

Part 3, Departure, focuses on Ali’s displacement and desire to find a home. He leaves Granada for Valencia to search for any remaining relatives. He was told they had gone to the village of Al-Jaafariya. However, they are not there, but he is welcomed by the sheikh, Al-Shatibi. Like his grandfather Hasan, Ali starts teaching children Arabic and passes on his knowledge to the next generation. He becomes infatuated with a girl named Kawthar, whose twin sister had been killed by the family in an honor killing. He searches for Kawthar in Valencia and finds her selling fish. Al-Shatibi and the rest of the village have washed their hands of her because she has told the Inquisitors about the murder. She does not reciprocate his love, marrying a Christian and having a child instead. Later, he is saddened to hear that she has been killed by her family.

Spanish colonial power seems to be waning. The crown imposes a new tax so they can fight the French. Sheikh Al-Shatibi rides to meet someone who has come back from Hajj. An impatient reader might feel that Ashour has gone off track when we are presented with the musings of a Hajj pilgrim who details his travels through Jerusalem and then through Egypt. Ali wonders, though, about the Crusaders and how this links to the idea of the Messiah. Ashour seems to imply that religious ideology should not be intertwined with political or state agendas. Earlier in the novel, Naeem also has this same thought when he sees how Catholic ideology is used to justify murder of Indigenous peoples in the New World.

The Arabs are being expelled once and for all and must leave through designated ports. Ali decides he will stay. Earlier, he had found the keys to one of the family’s houses when he pulled out papers from a cabinet. “Does one truly forget with time, as they say?” he wonders. “It’s not true. Time polishes the memory, as if it were water; you plunge gold in it for a day or for a thousand years, then you find it shining at the bottom of the river.”

Radwa Ashour’s wide-sweeping historical trilogy, set during a time of occupation for the Muslims of Spain, still shines like gold “at the bottom of the river.”

Cairo